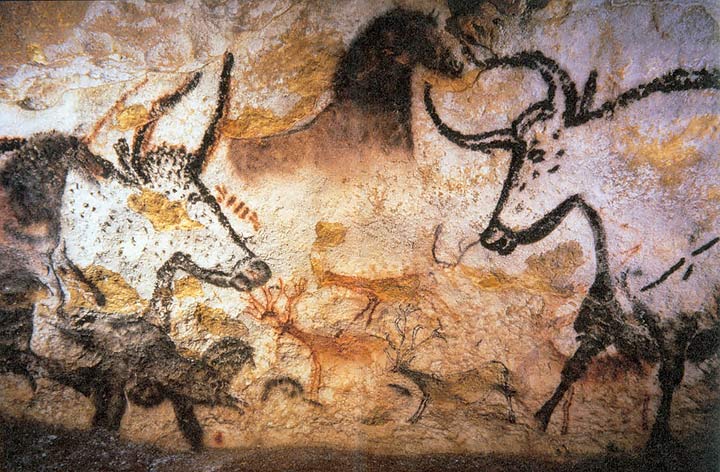

Last week we viewed the paintings of Altamira, also called the "Spanish Lascaux." Discovered too early by a father and daughter (who caught his attention by saying, "look, Daddy, oxen!") Saultola was ridiculed by leading prehistorians. The paintings are too colorful, too wonderful to have been made by Paleolithic artists--they must be fakes. This was typical of scholarly thought of the time, because believing the paintings were real would have turned theories of what prehistoric humans were capable of upside down.

We also examined the lifestyles of the people who painted the caves of southwestern France and northern Spain. Contrary to popular belief, these people were not just "big game hunters," but mobile foragers who made full use of available plants, small animals, birds, and fish to feed themselves. They also fashioned stone and bone tools, many decorated with pigment and incised designs, and had a complex system of geometric signs (National Geographic video on sign interpretation).

Whether the signs constitute an early form of language or writing is very much up for debate, but some signs--especially the red dots used on certain rock formations and near the end of passages clearly had meaning. Did the dots mean "great acoustic space," or "don't go any further, the cave gets dangerous"? No one knows.

One student sent me a video on the evolution of language, which discusses a theory that the key difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens is that the latter had full speech capability and that this gave modern humans a survival advantage over Neanderthals. The video is intriguing but does not take into account the most recent discoveries of Neanderthal capabilities for abstract thought and representational art. And scholars disagree about how much Neanderthals could speak: their vocal tracts were sufficiently developed for a range of one-syllable sounds which, when combined with geometric signs on painted walls and decorated objects, could have communicated a range of ideas.

More (New Scientist article 2016) on geometric signs and work of Genevieve von Petzinger

Whether the signs constitute an early form of language or writing is very much up for debate, but some signs--especially the red dots used on certain rock formations and near the end of passages clearly had meaning. Did the dots mean "great acoustic space," or "don't go any further, the cave gets dangerous"? No one knows.

One student sent me a video on the evolution of language, which discusses a theory that the key difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens is that the latter had full speech capability and that this gave modern humans a survival advantage over Neanderthals. The video is intriguing but does not take into account the most recent discoveries of Neanderthal capabilities for abstract thought and representational art. And scholars disagree about how much Neanderthals could speak: their vocal tracts were sufficiently developed for a range of one-syllable sounds which, when combined with geometric signs on painted walls and decorated objects, could have communicated a range of ideas.

More (New Scientist article 2016) on geometric signs and work of Genevieve von Petzinger